10 Iconic Brooklyn Books...

...that Every New Yorker Should Read

Betty Smith, Brooklyn native and author of nearly everyone’s first favorite book about Brooklyn—coming-of-age novels will do that for you—died 42 years ago today. To celebrate her life and literary legacy, here’s a selection of iconic books about Brooklyn that every New Yorker should read—if only to have an opinion on them one way or the other. Bear in mind that I’m not necessarily counting these the best books set in Brooklyn (though several of them are certainly among the best—Desperate Characters 4-ever), but they’re books that have achieved a certain, well, iconic status. Of course, even with that requirement, there are more than ten Brooklyn books that could fit the bill—Jonathan Lethem, Paul Auster, Michael Chabon, etc. are among these—so feel free to add further titles to the list in the comments.

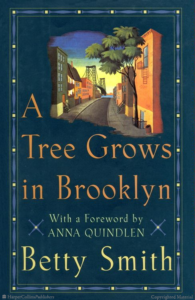

Betty Smith, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

Coming-of-age tales frequently wind up as icons of literature (think The Catcher in the Rye)—maybe because pretty much everyone eventually has to grow up in one way or another, so it’s hard not to relate. This one concerns the bright, curious Francie Nolan, 11 years old when the book begins, the child of first-generation Americans, who grows up in and out of a Williamsburg tenement in the early 1900s.

The one tree in Francie’s yard was neither a pine nor a hemlock. It had pointed leaves which grew along green switches which radiated from the bough and made a tree which looked like a lot of opened green umbrellas. Some people called it the Tree of Heaven. No matter where its seed fell, it made a tree which struggled to reach the sky. It grew in boarded-up lots and out of neglected rubbish heaps and it was the only tree that grew out of cement. It grew lushly, but only in the tenements districts. . . . That was the kind of tree it was. It liked poor people.

Paula Fox, Desperate Characters

The best book about rabies ever written, in my opinion. Also a pretty good one about gentrification, and class (with its attendant rules and pretensions), and this one particular couple: Otto and Sophie Bentwood. The Bentwoods live in a neighborhood in transition—the new maple trees are in blossom, but the streetlights are still smashed. A cat is wandering around, and when Sophie feeds it, it bites her. She more or less continues on with her business, except now wondering if she might have rabies. “God, if I am rabid, I am equal to what is outside,” she thinks. This is the crux of the book: the distinction between inside and outside, belonging and foreignness, safety and danger, and the question of whether there really are distinctions at all, or whether it’s all braided, inextricable.

With one or two exceptions, each of the houses on the Bentwoods’ block was occupied by one family. All of the houses had been built during the final third of the last century, and were of brick or brownstone. Where the brick had been cleaned, a chalky pink glow gave off an air of antique serenity. Most front parlor windows were covered with white shutters. Where owners had not yet been able to afford them, pieces of fabric concealed the life within behind nthe new panes of glass. These bits of cloth, even though they were temporary measures, had a certain style, a kind of forethought about taste, and were not at all like the rags that hung over the windows of the slum people. What the owners of the street lusted after was recognition of their superior comprehension of what counted in this world, and their strategy for getting it combined restraint and indirection.

One boardinghouse remained in business, but the nine tenants were very quiet, almost furtive, like the last remaining members of a foreign enclave who, daily, expect deportation.

Paule Marshall, Brown Girl, Brownstones

This classic novel—published in 1959 but really discovered by the culture at large in 1981 after being reprinted by the Feminist Press—is the story of a young girl living in a close-knit community of immigrants in Brooklyn during the Depression and World War II. Her father dreams of returning to Barbados, where he has inherited a piece of land; her mother wants him to sell it so they can buy the brownstone they live in. Another moving and insightful coming of age story that everyone should read.

The sun was always loud on Fulton Street. It hung low and dead to the pavement, searing the trolley tracks and store windows, bearing down until the street spun helplessly in an eddy of cars, voices, neon signs and trolleys. Selina responded to the turbulence, rushing and leaping in a dark streak through the crowd. Passing the beauty parlor she saw the new tenant Suggie and turned in.

James Agee, Brooklyn Is: Southeast of the Island: Travel Notes

Technically an essay, written in 1939 and only published nearly 30 years later, finally in book form. But it is still iconic, maybe as a kind of secret text, a lyrical meditation on the borough with all of its contradictions, beauties, and ugly marks.

Manhattan is large, yet all its distances seem quick and available. Brooklyn is larger, seventy-one square miles as against twenty-two, but here you enter the paradoxes of the relative. You know, here: only a few miles from wherever I stand, Brooklyn ends; only a few miles away is Manhattan; Brooklyn is walled with world-traveled wetness on west and south and on north and east is the young beaver-board frontier of Queens; Brooklyn comes to an end: but actually, that is, in the conviction of the body, there seems almost no conceivable end to Brooklyn; it seems, on land as flat and huge as Kansas, horizon beyond horizon never unfolded, an immeasurable proliferation of house on house and street by street; or seems as China does, infinite in time and patience and in population as in space.

Hubert Selby Jr., Last Exit to Brooklyn

This cult classic is a kind of hard-core reading gauntlet, a tough-talking portrait of the down-and-out in Brooklyn in the 1950s—replete with junkies, prostitutes, criminals, and those living among them.

The bodies went back in the doors and bars and the heads in the windows. The cops drove away and Freddy and the guys went back into the Greeks and the street was quiet, just the sound of a tug and an occasional car; and even the blood couldn’t be seen from a few feet away.

Alfred Kazin, A Walker in the City

Kazin’s 1951 memoir about growing up in Brownsville in the 1920s and early 1930s, the first American in a family of Jewish immigrants, is a classic of Jewish-American literature, but also a feat of vivid prose that makes real both the briny smells of the neighborhood and the incessant lure of “the city,” so close and yet so far away.

Everything seems so small here now, old, mashed-in, more rundown even than I remember it, but with a heartbreaking familiarity at each door that makes me wonder if I can take in anything new, so strongly do I feel in Brownsville that I am walking in my sleep. I keep bumping awake at harsh intervals, then fall back into my trance again. In the last crazy afternoon light the neons over the delicatessens bathe all their wares in a cosmetic smile, but strip the street of every personal shadow and concealment. The torches over the pushcarts hold in a single breath of yellow flame the acid smell of half-sour pickles and herrings floating in their briny barrels. . . . The sudden uprooting I always feel at dusk cries out in a crash of heavy wooden boxes; a dozen crates of old seltzer bottles come rattling up from the cellar on an iron roller. Seltzer is still the poor jew’s dinner wine, a mild luxury infinitely prized above the water out of the faucets; there can be few families in Brownsville that still do not take a case of it every week. It sparkles, it can be mixed with sweet jellies and syrups; besides, the water in Europe was often unclean.

Jay-Z, Decoded

Admittedly little more modern than most of the books on this list, but hey—Brooklyn’s changing every day. Jay-Z is one of its most beloved sons (and icons), and his 2010 book, part memoir, part cultural commentary, part deconstruction of his own art, holds its own next to him.

I saw the circle before I saw the kid in the middle. I was nine years old, the summer of 1978, and Marcy was my world. The shadowy bench-lined inner pathways that connected the twenty-seven six-story buildings of Marcy Houses were like tunnels we kids burrowed through. Housing projects can seem like labyrinths to outsiders, as complicated and intimidating as a Moroccan bazaar. But we knew our way around.

Marcy sat on top of the G train, which connects Brooklyn to Queens, but not to the city. For Marcy kids, Manhattan is where your parents went to work, if they were lucky, and where we’d yellow-bus it with our elementary class on special trips. I’m from New York, but I didn’t know that at nine. The street signs for Flushing, Marcy, Nostrand, and Myrtle avenues seemed like metal flags to me: Bed-Stuy was my country, Brooklyn my planet.

L.J. Davis, A Meaningful Life

Once all-but-forgotten, but recently reissued by the always-excellent NYRB, A Meaningful Life is another darkly funny book about gentrification: a deeply bored and unfulfilled man decides to spend all the money (and time, and energy) he has on a run-down Brooklyn house in a run-down neighborhood, with the idea that if he can fix this house, he can fix everything, and finally live right. It turns out to be rather more difficult than that.

Spring came exhaustingly that year, almost as though something were leaving his life rather than entering it, and in the cold April sunsets the house took on the devastated look of the streets, as if it had been attacked, not recently but months ago, bu a squad of compulsively tidy commando assassins, who had raced up and down the stairs, chucking grenades into every room, and then had cleaned up after themselves. Where partitions had been, there were jagged outlines on the walls. Nothing remained in the bathrooms but the heads of pipes. Holes were scattered here and there in the walls, in the ceilings, in the floors. Lowell couldn’t remember why he’d made some of them. There must have been a good reason. Electric blue in one room, green in another, shattered and stripped, the house didn’t look as though Darius Collingwood had ever conceived it, or that the poor people had ever occupied it, or that Lowell was ever going to live in it. It looked ready to be demolished. A weekend came, and Lowell wandered out in the back to look at his pile of linoleum again.

Jacqueline Woodson, Another Brooklyn

Perhaps this one isn’t officially iconic yet, considering it was only published in 2016. But Woodson herself is certainly already iconic, and I have a good feeling about the long-term future of this novel, which is about girlhood in 1970s Brooklyn, and friendship, and family, but is as much, if not more, about memory.

Somehow, my brother and I grew up motherless yet halfway whole. My brother had the faith my father brought him to, and for a long time, I had Sylvia, Angela, and Gigi, the four of us sharing the weight of growing up Girl in Brooklyn, as though it was a bag of stones we passed among ourselves saying, Here. Help me carry this.

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

Well, it really doesn’t get more iconic than Whitman, Brooklyn’s most famous poet. His magnum opus includes, among other things, the incendiary poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.”

What is it then between us?

What is the count of the scores or hundreds of years between us?

Whatever it is, it avails not—distance avails not, and place avails not,

I too lived, Brooklyn of ample hills was mine,

I too walk’d the streets of Manhattan island, and bathed in the waters around it,

I too felt the curious abrupt questionings stir within me,

In the day among crowds of people sometimes they came upon me,

In my walks home late at night or as I lay in my bed they came upon me,

I too had been struck from the float forever held in solution,

I too had receiv’d identity by my body,

That I was I knew was of my body, and what I should be I knew I should be of my body.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.